Samizdat Podcast with Natalia Gârbu

Natalia Gârbu is a photographer, artist and the creator of Mahala magazine.

Eva Mocanu from Samizdat Podcast, in conversation with Natalia:

You said a long time ago, back in 2015, in an article published on locals.md, that you think a living artist is an experimenting artist. You are a professional photographer, and starting from this thought you stated 6 years ago, tell us what other art forms you love and practice besides photography.

As an artistic person you feel the world around you and you want to understand where your place is. My path for self understanding happened by means of several techniques and projects that I keep inventing and here I still find the courage to keep doing them. First it was collage making, now the magazine, but at core I am a documentary photographer.

Are you self-taught or have you done your studies somewhere?

I learned the collage myself, and photography — I have done my studies in Barcelona consisting of perception studies. That’s where my view of people and my own life changed.

Here Natalia mentioned a curious thought about being “the best”. Barcelona taught her not to think she was the best, as mothers or fathers love to tell their children: you are the most beautiful girl, you are the smartest boy. Barcelona carved this in stone for Natalia and now she says “everything is ok, I’m not the best…and my goal is not to become the best woman or photographer”.

Natalia Gârbu’s personal archive

You used to take pictures of the mosaics in Moldova and document them. Does this attempt to document Moldovan artifacts continue?

No, that was about 8–10 years ago when I started documenting the mosaics, beginning with the northern part and in a year they had already disappeared, meaning someone demolished them. I felt useless at that point and the documentation no longer fascinated me. That left a not very pleasant feeling and I don’t even want to look through these photographs with mosaics anymore. I think I’ll eventually get over this, but now it’s still unpleasant.

I don’t want to document artifacts anymore, but as for documenting people — yes. I think lately I’ve been focused more on people, their stories and memories rather than objects.

Let’s talk about Mahala magazine: How was the idea born and where did the desire and the need come from?

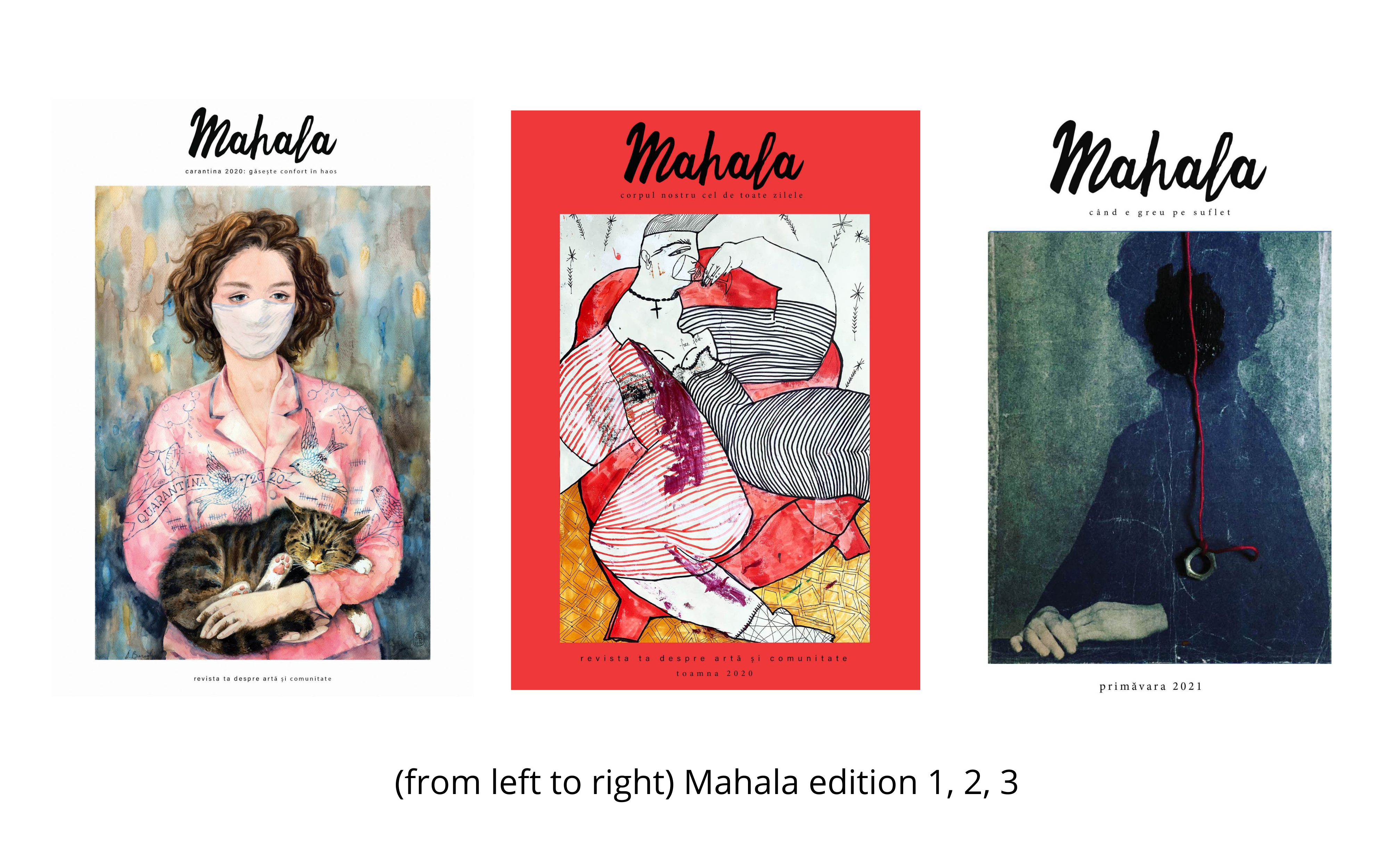

I think Mahala is a kind of escapism. The moment we were forbidden to leave the houses, my beloved phrase remained “with me inside me” (cu mine-n mine) and there was something to be done about it. Initially, I really wanted to publish my photos on paper, not to see them on the screen, and after that, I gathered a bunch of people with whom I did the first issue together. The first magazine appeared in March 2020, during the pandemic.

Have you been thinking for a long time that you want it to be a magazine, a format like this, or was it born spontaneously?

Spontaneously. I told you earlier that I have no problem with courage — an idea comes to me — I execute on it. I don’t know if unfortunately or fortunately, but I think a little about the impact and what someone else will think about what I do, and that’s why everything works out easily for me. That is why Mahala was not a well thought project, it was a spontaneous project where we gathered, worked and moved on. The second issue of the magazine has already been focused on experiences that are painful to us or may have hurt at some point.

Where does the idea of the name “Mahala” come from? Someone from my neighbors in Strășeni, where I was isolated during the pandemic, created a group called Mahala Aleea Plopilor, and from there came the word itself — Mahala. And I was thinking about the fact that we no longer communicate with each other. Somehow, we introverted a lot and we consider that a very good norm and excuse — I’m an introvert, sorry.

How can you not love sincere interactions with neighbours?! Nobody really asks you to spend a lot of time explaining your personal life to them. Relationships with neighbours are connections that cause electricity that gives you more well-being.

Mahala’s idea was taken out of this context — to bring more people together.

Natalia Gârbu’s personal archive

Natalia Gârbu’s personal archive

The word Mahala or Mahalla is used in many languages and countries meaning neighbourhood or location originated in Arabic محلة mähallä, from the root meaning ‘to settle’, ‘to occupy’ derived from the verb halla (to untie). Mahala is also a Balkan word for “neighbourhood” or “quarter”, a section of a rural or urban settlement, dating to the times of the Ottoman Empire. Source: definitions.net

Why would we unite in a creative community, don’t we all feel better as separate entities?

Mmm, I don’t know what we can do separately. I think once we realize we’re a whole lot… my grandfather used to say that if I threw the candy papers down the street, that could become an epidemic and everyone would start throwing the candy papers down, too. Once one of us stops, a whole vicious circle might stop. The Corona virus has shown us that we are very close to each other.

Natalia Gârbu’s personal archive

We talked a little about the community in Barcelona, where Natalia said that it was even harder to be part of a community, because the moment you went out for a beer with one person, the same person would leave for another country in half a year or less. Natalia confessed to us that her return home was due to the thought that she was returning to a better Moldova, which turned out to be only in her imagination at that time.

Mahala magazine is a kind of inspirational magazine. In it you can find discussions about art and creativity, Moldova and the community. How does this zine differ from Locals.md for example? (apart from the fact that it is printed)

I don’t think Mahala has even blossomed yet, because no one on my magazine team knows how to make a magazine. I don’t think I can talk about the Mahala now as a final product, because it’s just the beginning. I can’t even compare it to anything because it doesn’t even have a certain style, but I think that Mahala will develop and be a nice finished product.

When you gave birth to this idea with your team, were you inspired by other zines, magazines, or were you very independent in your decision

We had no outside sources, it happened as we felt and it was created from all the ideas we had. A super honest project in this context.

What is it like to work with local printing houses?

OMG, an easier question?! I keep trying them, because I recently had a case in which, I admit that it is my fault too, I did not check if everything was written correctly, as a result I had to wait for half a year for a product that could not be released to the public.

In addition to magazines, there are other materials that can be purchased. Maybe you want to tell us about them.

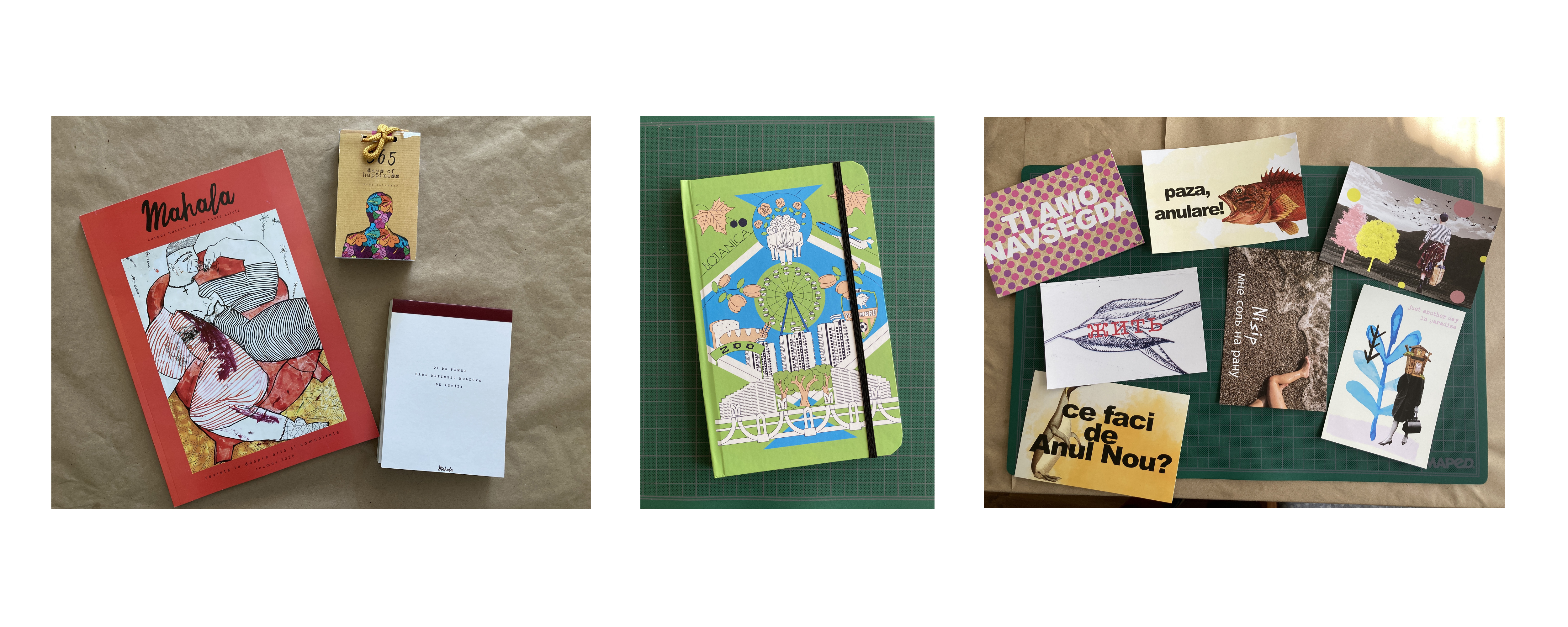

It’s a kind of a merch that can make the magazine survive, because the magazine can’t bring in revenue if you don’t have advertising in it. We include money-free advertising in the magazine where we simply decided to help all sorts of local artisans, that’s why the merch helps us to continue to exist and create. In the case of Mahala, the merch is the calendar, the postcards, the notebooks.

Speaking of covers, the first magazine is the illustration of Aliona Bereghici, the second of Natalia Romanciuc. How did you work with the women — did they come to you or did you contact them?

We knocked on their doors and asked them to cooperate. Aliona Bereghici was nice to us and trusted some strangers, sharing her illustration for the cover. We consider that illustration she made to be very representative of the pandemic period. And the second illustration was very representative for me, because I had gained a lot of weight after the quarantine and this glass of wine I think everyone can visualize during the quarantine.

Perhaps you have some recommendations for online zines / magazines that you would like to share with us?

You know, I have two magazines at home that may have marked me subconsciously and one of them is NOUĂ magazine. I believe that I have never seen a more beautiful project like NOUĂ in Moldova. I still browse this magazine, and the topics in it remain as current and, in my dreams, I want Mahala to look at least a little like NOUĂ. But I understand what kind of budget is necessary for such projects.

The day before our discussion, Natalia posted on Facebook the appearance of a new Mahala edition. We asked her what feelings she had about the new magazine, to which she replied that this edition is the most sincere because 80 percent of the magazine is made by her and she is quite stressed about it.

Do you take the budget out of your own pocket?

Yes, and the merch somehow closes certain expenses, because when you print magazines, you normally don’t print only 100 units, because you pay 400 lei per magazine, you have to print at least 300–500. Of course, our purchasing power is not so great and they remain unpurchased, so yes, this is a project from our own sources.

Where can we find and buy the Mahala magazines?

In all the fine bookstores — Cărturești, Cartego and I hope that waters will clear somehow and for us to find a few more partners and points of sale. And on the website, of course — mahala.shop

About the Mahala team

My team sometimes changes, sometimes not, so it’s about the person who makes the correction — Ana-Maria Lavric, Galina Roșca who will continue to help us get further at festivals, yard sales; it’s Ecaterina Postolachi who finds people and stories, there was also someone else who has helped us with instagram so far. The team constantly changes, someone joins — someone leaves.

This is where Anna joined the discussion. She asked Natalia about the magazine, namely that the magazine oscillates between community work and Natalia’s personality. Natalia admitted that the magazine leans more towards her, because not being a designer, she tries to model it herself and ends up taking the thing far too personally. Natalia talked about the fact that the price for the magazine can be high for Moldova, but by buying the magazine or the merchandise, the buyer financially supports the life of the magazine, making its continuity possible.

Tell us about “21 women who define today’s Moldova” (21 de femei ce definesc Moldova de astăzi), a wonderful project that appeared this spring.

Tell us about “21 women who define today’s Moldova” (21 de femei ce definesc Moldova de astăzi), a wonderful project that appeared this spring.

It is an annual project that we hope to carry out every March — we publish a booklet with the 21 women (in 2021), 22 women (in 2022) which really define Moldova and have the courage to do what they do and remain to be themselves. We appealed to 21 designers and painters and they illustrated the 21 women, with a total of 42 women we are proud of.

But who chose these 21 women?

We created a questionnaire on the Internet in which we asked the community who in their opinion represents us now, who defines today’s Moldova and from the answers received, we developed the list that was illustrated after.